Habibiz

Curated by Jessica Kirk + Mitra Fakhrashrafi

Following the Shisha Ban which came into effect on April 1st, 2016 and has since forced nearly 70 predominantly Black and Brown migrant-owned businesses to close and/or restructure their livelihoods, the owner of Kennedy Road’s Very Own Habibiz Shisha Lounge asks, “where else is there for us in this city?” [1]. Through mixed media, poetry, and audio-based instillations, Habibiz asks:

“What does it mean to illegalize already hypersurveilled spaces and communities?

How do Black, Indigenous and racialized people reckon with the familiarity of being re/moved?

As Toronto changes and places of sanctuary are brought down/underfunded/renovicted, how do we preserve stories and physical spaces (safely or otherwise)?”

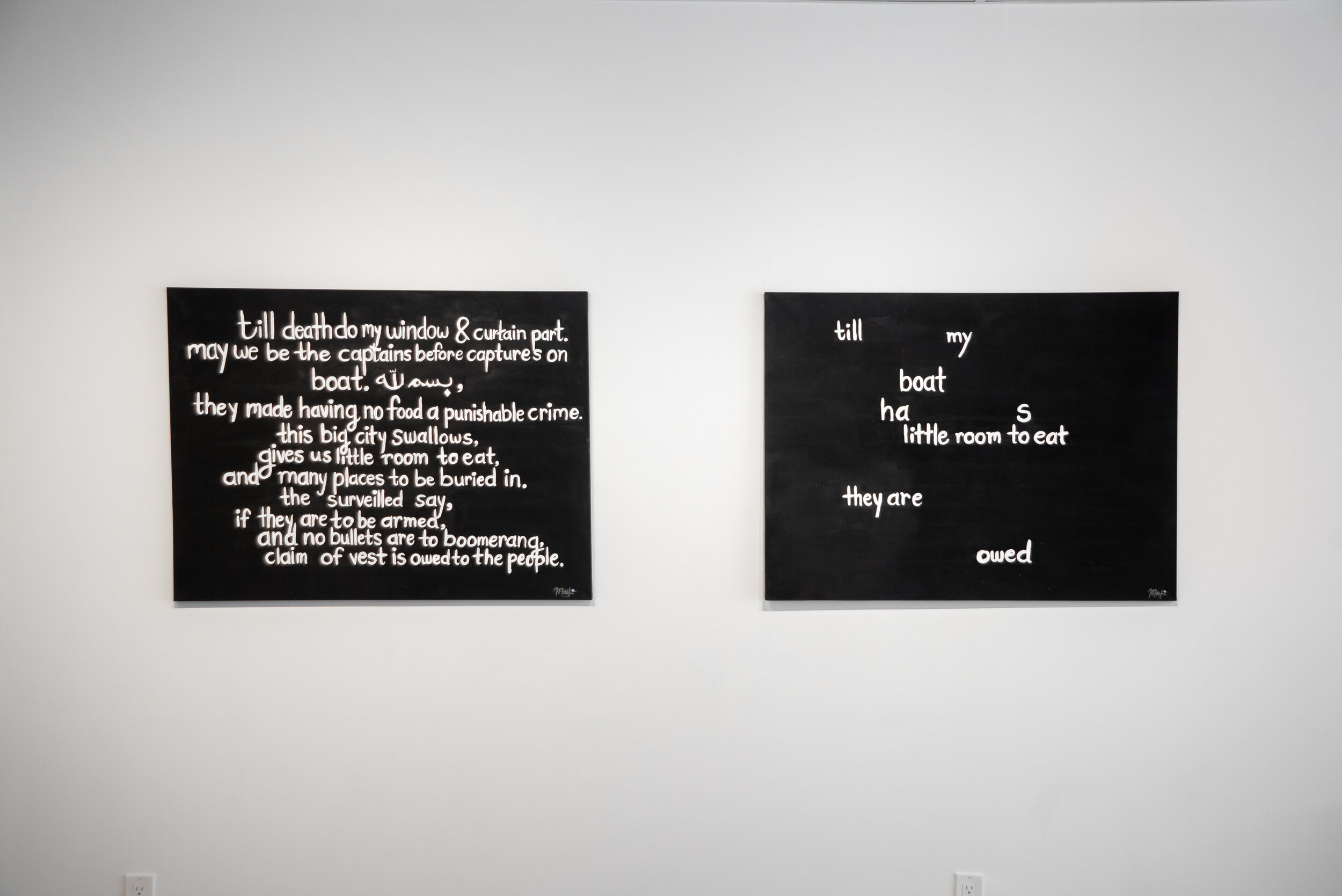

“Visa” (2019), Mahdi Chowdhury

Through Habibiz, Way Past Kennedy Road aims to centre racialized and spatialized understanding of placemaking which transform “the places in which we find ourselves into places in which we live”[2]. We draw from what Black, Indigenous and racialized people have to say about access, movement and forced displacement in the Greater Toronto Area (GTA), confronting normalization of community destruction through laws enacted, bans established, and the “stress of living in a metropolis actively pricing out its residents”[3]—all of which have roots in surveillance[4]. These changes are meaningful to the people who frequent rejected corners of the city: strip malls, shisha lounges, and nail salons alike. We locate the shisha lounge as a site of intergenerational gathering, a site of migrant ownership, and a site of placemaking for Black and/or Muslim people. The stories shared through the exhibit take the ordinary, the things Amani Bin Shikhan describes as “bordering on mundane”[5], highlighting them both as places of surveillance and places where “otherwise oppressive geographies of a city can provide sites of play, pleasure, celebration [and life].” [6]

where now? (2018), Amani Bin Shikhan with sisterhood media

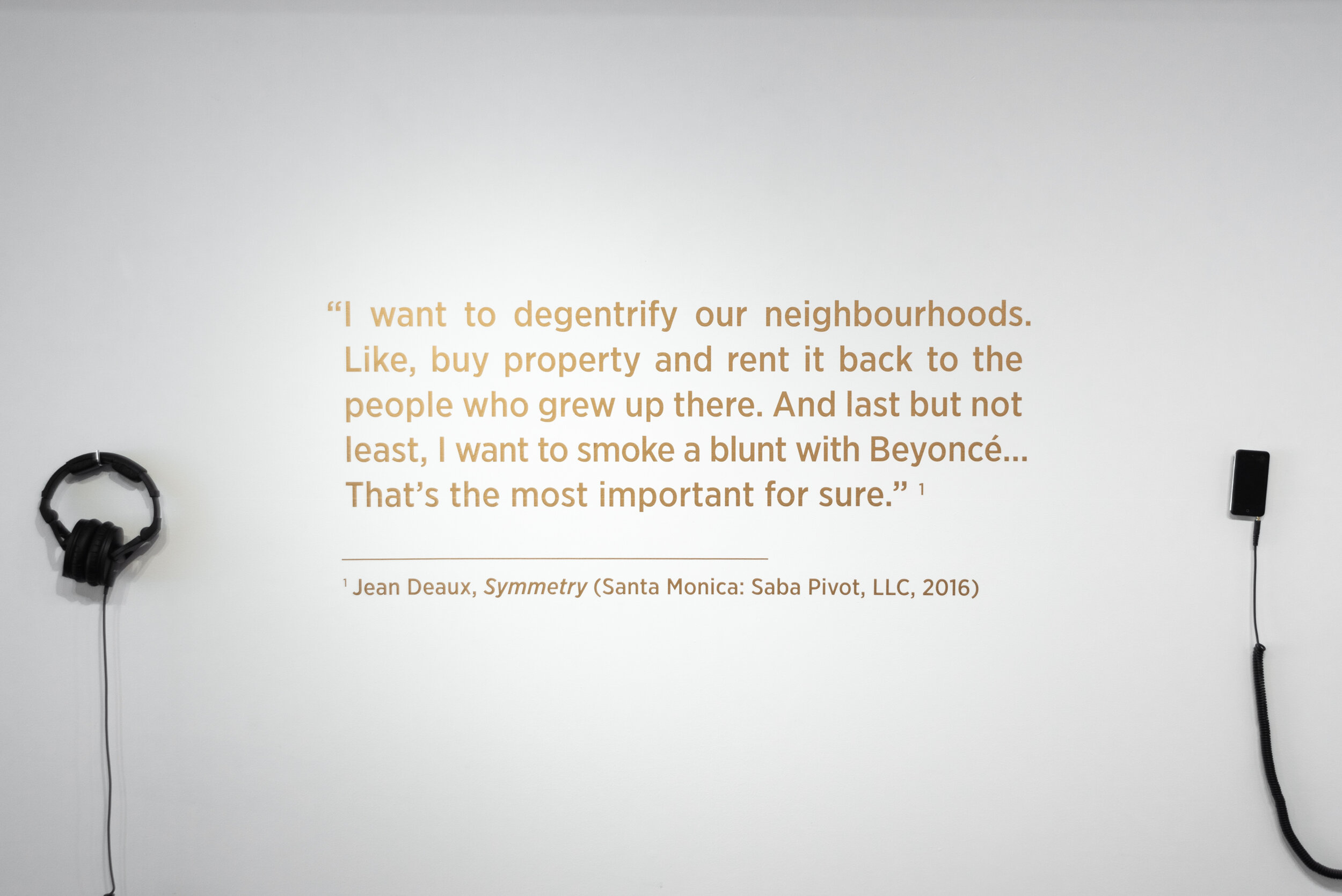

In conversation with Najma Sharif, Halima S. Gothlime responds to questions on “how to create—and even just exist—in spite of”[7] forces trying to suppress and outright ban [Muslim Somali women] from public spaces, describing surveillance as “an organism trying to regulate how and where things are placed”. Through photography, Mahdi Chowdhury [8] interrogates the way surveillance is deeply felt as regulation at borders where visas are used to submit to state surveillance and/or become subject to statelessness. Through a series of .gifs, Idil Djafer [9] traces the way surveillance is deeply felt as regulation in Toronto since the majority of spaces she enters in this ever-gentrifying city are white spaces/negative spaces. Rather than seeing surveillance as something newly inaugurated by technologies such as automated facial recognition and digital data collection, the artists of Habibiz insist on factoring how “racism and anti-Blackness undergird and sustain existing surveillances” [10], continuously shaping access, movement, and forced displacement.

“In extending a conversation on radical traditions of placemaking across the GTA, the works reckon with and/or suggest alternative ways of living under routinized surveillance. ”

At Digital Justice Lab’s ‘Alternative Urban Futures’, Michelle Murphy [12] challenged smart cities projects by asserting that Indigenous land protectors, sex workers and other people who are experts on breaches of consent should be at the forefront of discussions around city infrastructure. We extend Murphy’s call to action by insisting that communities who are often pushed to the periphery should be at the forefront of creating core value systems for this ever-shifting city. Using the Shisha Ban to extend a broader discussion on both placemaking and surveillance with artists and community organizers in Toronto and Chicago, through Habibiz we are offered the space to archive complicated histories and futures of Black, Indigenous, and racialized life in the city. Click here to access “habibiz: the official playlist”.

Accompanying programs: The Feeling of Being Watched (2017) screening, Curator talk and button making session presented with Platform A, Digital Justice Lab workshop facilitated by Nasma Ahmed.

Works cited

[1] Huda Hassan, “Banning Shisha in Toronto is About A Lot More Than Health Codes in Fader (2016).

[2] Lynda Schneekloth and Robert Shibley, Placemaking: The Art and Practice of Building Communities (1995).

[3] Amani Bin Shikhan, where now? guestbook note(2018).

[4] Ifrah Amhed in conversation with Najma Sharif, “5 Somali Creatives on How Surveillance Culture Shapes Their Work” in NYLON (2018).

[5] Amani Bin Shikhan, where now? guestbook note (2018).

[6] Marcus Anothy Hunter et al., Black Placemaking: Celebration, Play, and Poetry in Theory, Culture, and Society (2016).

[7] Najma Sharif, “5 Somali Creatives On How Surveillance Culture Shapes Their Work” in NYLON (2018).

[8] Mahdi Chowdhury, Videre (2019).

[9] Idil Djafer, Not Our Space (2019)

[10] Simone Browne, Dark Matters: on the surveillance of Blackness (2015).

[11] ibid.

[12] Michelle Murphy at the “Alternative Urban Futures” symposium (2018).

Press

Land Marks: Subversive Cartography Maps the Margins by Adwoa Afful in Bitch Media (Summer 2019, print)